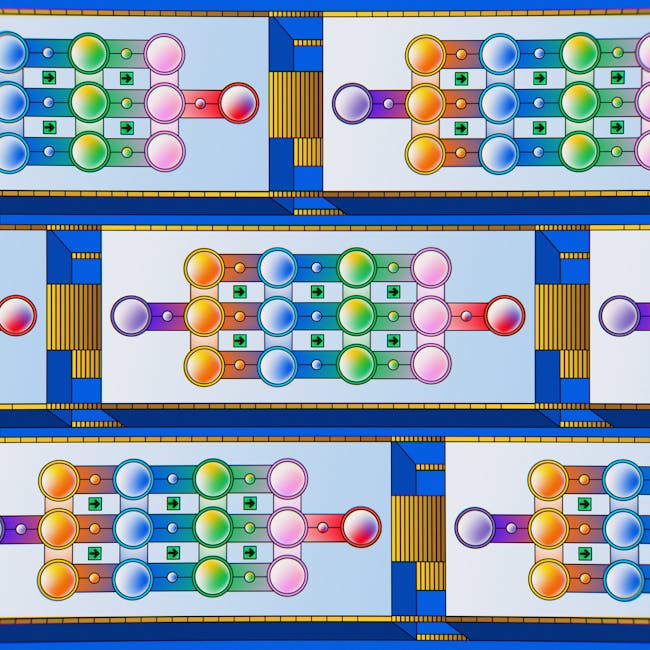

The rise of Decentralized Exchanges (DEX) has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of crypto trading, offering transparency and self-custody that traditional centralized platforms cannot match. However, the operational mechanics—especially those involving high-volume activity—differ significantly from traditional finance and centralized crypto exchanges (CEX). For sophisticated traders, understanding The Role of Order Books in Decentralized Exchanges (DEX) and High-Volume Crypto Trading is essential for optimizing execution and minimizing costs. While many successful DEXs employ Automated Market Makers (AMM), the most competitive high-volume trading platforms in DeFi are now converging toward versions of the Central Limit Order Book (CLOB), mimicking the structure detailed in our foundational guide on The Ultimate Guide to Reading the Order Book: Understanding Bid-Ask Spread, Market Liquidity, and Execution Strategy, but with significant on-chain constraints.

The Evolution of Order Books in Decentralized Exchanges (DEX)

Historically, the major impediment to implementing a true CLOB on-chain was performance. Placing, updating, or canceling an order requires a verifiable transaction, which, on early blockchains like Ethereum, was prohibitively slow and expensive. This led to the dominance of AMMs (e.g., Uniswap), which use bonding curves rather than discrete bids and asks. However, high-volume traders require the precise execution and detailed liquidity insights that only an order book provides. This necessity has driven the development of several innovative models:

- Fully On-Chain CLOBs (Layer 1/L2 Solutions): Platforms built on high-throughput chains (like Solana, Aptos, or specific Layer 2 solutions) can handle the transaction volume required for continuous order matching. These platforms record every bid and ask directly on the ledger.

- Hybrid CLOBs (Off-Chain Matching, On-Chain Settlement): Platforms like dYdX or some StarkWare-based systems use an off-chain sequencer to manage the order book matching process (achieving sub-millisecond latency), while settlement and custody remain verifiably decentralized on-chain. This balances speed with security.

- Concentrated Liquidity Market Makers (CLMMs): While not strictly order books, newer AMM models (like Uniswap V3) allow LPs to concentrate liquidity at specific price ranges, effectively mimicking deep order book tiers, but the execution strategy remains different for traders.

For high-volume traders employing limit orders and seeking to analyze market structure, focusing on the true CLOB implementations—whether hybrid or fully on-chain—is critical. The analysis of the Depth of Market (DOM) visualization on these platforms provides crucial insight into where liquidity truly rests.

Operational Challenges Unique to Decentralized Order Books

Trading high volume on a DEX order book requires acute awareness of costs and technical constraints that are absent in CEX environments.

Gas Costs and Transaction Overhead

In a CEX, placing a limit order is free. On a DEX (especially those with higher gas costs), every action is a transaction:

- Order Placement: Costs gas.

- Order Cancellation: Costs gas.

- Order Update/Modification: Costs gas.

This reality severely impacts scalping strategies and high-frequency trading (HFT) that rely on frequent, rapid order adjustments. A large trader must factor the cumulative gas cost into their profitability analysis, often making it uneconomical to place or adjust small, tight-spread orders. This contributes to wider effective spreads compared to zero-fee CEXs.

Latency, Finality, and Market Microstructure

Even the fastest Layer 1 blockchains still have block times measured in hundreds of milliseconds to several seconds, far slower than the microsecond speeds of centralized exchanges. This latency:

- Increases Risk: The time between submitting an order and its inclusion in a block creates a large window for market conditions to change, increasing the risk of detrimental slippage, especially during volatility.

- Limits Execution Speed: True HFT cannot exist on slow chains. High-volume traders must focus on medium-frequency strategies or use highly optimized hybrid DEXs where matching occurs off-chain.

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) and Order Manipulation

MEV is perhaps the most significant structural risk for high-volume traders on decentralized order books. Searchers (specialized bots) monitor the mempool for pending transactions, including large limit or market orders. They can then:

- Front-run: Placing their own order ahead of the large pending order, ensuring they execute first at a more favorable price.

- Sandwich Attack: Placing an order before and after a large market order, capturing the price movement caused by the large trade.

Reading the order book on a DEX must therefore be coupled with an awareness of potential MEV attacks, which function similarly to spoofing and iceberg orders but are executed permissionlessly by network participants rather than malicious institutional actors.

Order Book Analysis for High-Volume DEX Trading

The ultimate goal for a high-volume trader is to execute a large position without unduly moving the price. On a DEX CLOB, the strategy revolves around assessing effective liquidity—the amount of volume available at the quoted price, minus the costs of execution (gas and slippage).

Gauging Effective Liquidity via Cumulative Depth

A high-volume trader should look beyond the top of the book and analyze the cumulative depth. This involves:

- Identifying “Walls”: Large, clustered orders on either the bid or ask side that indicate significant support or resistance. On a DEX, these walls are more reliable than CEX walls because the gas cost of placing and canceling them deters casual spoofing.

- Calculating Fill Price vs. Gas Cost: When executing a large market order (or a large fill-or-kill limit order), the trader must simulate the path of execution through the order book tiers and add the fixed gas cost to the average execution price. If the gas cost consumes a significant portion of the intended profit, the trade is not viable.

- Monitoring Spread Volatility: The bid-ask spread on a DEX CLOB often widens dramatically during high volatility, reflecting the market makers’ difficulty in quickly adjusting quotes due to transaction latency and costs. This is the optimal time to use carefully placed limit orders rather than aggressive market orders.

The Strategic Use of Limit Orders

Given the risks of MEV and high slippage, high-volume traders should prioritize limit orders over market orders whenever possible. However, the limit order must be strategically placed to offset the gas cost of placing and potentially canceling it.

Actionable Insight: High-volume traders on DEX CLOBs often place their limit orders deeper in the order book (away from the current spread) during quiet periods, aiming to be filled passively when volatility returns, thus avoiding the high gas cost of constantly adjusting their position near the midpoint.

Case Studies: High-Volume Execution on CLOB DEX Platforms

Case Study 1: Arbitrage on dYdX (Hybrid Order Book)

dYdX utilizes an off-chain CLOB for matching and risk management, which allows it to achieve latency comparable to centralized exchanges while maintaining on-chain custody and settlement. A high-volume arbitrage fund seeking to exploit a price discrepancy between Binance and dYdX would:

- Analyze Liquidity Depth: Use the dYdX order book visualization to instantly determine the volume available at the top 5-10 price levels.

- Strategy: Since gas costs are managed efficiently (often subsidized or batch-processed in L2 rollups), the fund can use large, aggressive limit orders placed just outside the spread to capture most of the desired volume quickly.

- Benefit: The low latency ensures the arbitrage window is captured before it closes, and the detailed order book structure allows the fund to model the exact price impact (slippage) with high precision before committing capital.

Case Study 2: Large Block Trades on Solana DEX (Fully On-Chain CLOB)

Blockchains like Solana offer extremely low transaction fees, making frequent order placement and cancellation viable, even for smaller traders. However, during periods of peak network congestion (e.g., major token launches or high volatility), blocks can still be delayed.

A quantitative trader needing to execute a $10 million trade of a volatile pair (e.g., SOL/USDC) would:

- Monitor Block Finality: Prioritize trading only when network health metrics (transaction finality time) are stable.

- Iceberg Strategy Adaptation: Due to the risk of MEV and network congestion, the trader employs an adapted Iceberg strategy. Instead of relying on the system to break the order, the trader manually places a series of small limit orders (tranches) deeper into the book, ensuring that each tranche is less than 1% of the total available depth at that price.

- Risk Mitigation: This avoids signaling the full size of the trade to MEV bots and prevents the entire trade from failing due to one congested block submission, allowing for smooth, decentralized execution.

Conclusion

The order book remains the most powerful tool for analyzing market intent, liquidity, and potential execution costs, even in the complex, constraint-ridden environment of Decentralized Exchanges. For high-volume crypto traders, success on DEX CLOBs hinges on adapting traditional order book strategies—such as analyzing the bid-ask spread and cumulative depth—to account for unique decentralized factors like gas costs, latency, and the pervasive threat of MEV. Mastering this analysis is a specialized skill that offers a significant edge in navigating the future of decentralized finance. For a comprehensive understanding of the foundational principles underpinning all order book analysis, revisit the core concepts in The Ultimate Guide to Reading the Order Book: Understanding Bid-Ask Spread, Market Liquidity, and Execution Strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about DEX Order Books and High-Volume Trading

Q1: How do order book DEXs (CLOBs) differ fundamentally from AMMs for high-volume traders?

CLOB DEXs provide discrete price levels and explicit volume depth, allowing high-volume traders to calculate precise slippage and place targeted limit orders. AMMs use mathematical curves, leading to predictable but often high slippage on large trades, and do not offer the detailed market microstructure analysis that order books afford.

Q2: Why are gas costs so crucial when analyzing the DEX order book?

Gas costs act as a minimum hurdle for profitability. They discourage frequent, micro-adjustments to limit orders, leading to wider effective spreads and potentially less dense liquidity near the midpoint. For a high-volume trader, gas costs must be subtracted from the captured spread to determine the true profit margin.

Q3: Can sophisticated traders still detect manipulation like Spoofing on a DEX order book?

Traditional spoofing (placing large orders with no intention of execution) is less common on fully on-chain CLOBs because the cost of placement and cancellation deters it. However, the DEX equivalent is often represented by Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) attacks, where bots manipulate the ordering of transactions in the mempool to front-run or sandwich large orders, which requires advanced chain-data monitoring rather than just order book visualization.

Q4: How does latency impact the accuracy of reading a DEX order book compared to a CEX?

DEX order books, especially fully on-chain versions, are updated only upon block finalization (seconds), whereas CEX books update in milliseconds. This time delay means the DEX order book visualization might not represent the absolute real-time state, increasing the risk of executing a large market order into rapidly shifting liquidity, which relates directly to minimizing slippage, as discussed in Minimizing Slippage: Using Bid-Ask Spread Data as a Strategy Filter During High Volatility Events.

Q5: Is it safe to place large limit orders close to the top of a DEX order book?

Placing large limit orders near the current price is risky on a DEX due to the high likelihood of being targeted by MEV front-running bots. These bots can detect your order in the mempool and execute trades to capture the favorable movement your large order creates. High-volume traders often prefer to use specialized MEV-protected relays or break up their orders into smaller, less noticeable tranches.

Q6: What is the concept of “effective liquidity” on a DEX order book?

Effective liquidity is the volume available at a given price level after accounting for all execution costs, including transaction fees (gas) and estimated MEV impact. A high-volume trader must calculate the effective liquidity because high gas fees can render a seemingly deep order book uneconomical for execution.

Q7: How do decentralized market makers utilize the order book to provide liquidity?

Decentralized market makers, like their centralized counterparts, aim to capture the spread. They use high-speed infrastructure to quickly place and cancel limit orders on both sides of the book. However, they must programmatically adjust their quoting strategy to account for gas costs and high volatility, minimizing the risk of being picked off during network congestion, similar to the techniques detailed in How Market Makers Use the Order Book to Provide Liquidity and Capture the Spread Profitably.