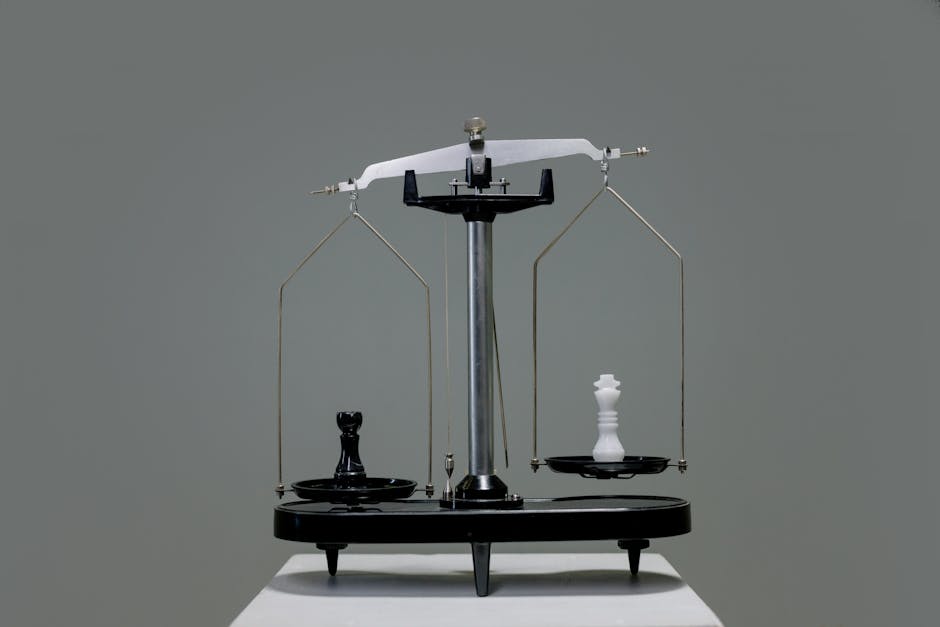

Futures contracts are among the most versatile and powerful financial instruments available, but their complexity often masks the simple duality behind their existence. At their core, these contracts facilitate two distinct, yet interdependent, market functions: the transfer of price risk and the assumption of price risk. Understanding the differences between Hedging vs. Speculation: Two Primary Uses of Futures Contracts is fundamental for any beginner seeking to navigate this complex asset class. While both practices utilize the same tools—standardized contracts traded on centralized exchanges—their motivations, risk profiles, and operational goals are worlds apart. For a broader overview of how these tools function, including margin and risk management principles, refer to The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide to Futures Trading: Contracts, Margin, and Risk Management Explained.

Hedging: The Goal of Risk Mitigation

Hedging is the defensive use of futures contracts. It is employed by commercial participants—producers, manufacturers, processors, and institutional investors—who have an existing exposure to price fluctuation in the underlying physical or financial asset. The core purpose of hedging is not to generate profit from price changes, but rather to minimize, or eliminate, the risk of adverse price movements occurring between the present day and a future date when the actual transaction (sale or purchase) will take place.

The Mechanism of Risk Transfer

A hedger uses futures to lock in a price today. If a corn farmer knows they will harvest 10,000 bushels of corn in three months, they are vulnerable to the price of corn falling before the harvest. To hedge, the farmer sells (goes short) the equivalent amount of corn futures contracts today.

- If the price falls: The loss incurred in the physical market (selling the crop for less) is offset by the profit made in the futures market (buying back the short contract at a lower price).

- If the price rises: The profit gained in the physical market (selling the crop for more) is offset by the loss incurred in the futures market (buying back the short contract at a higher price).

In essence, the hedger sacrifices potential upside profit in exchange for protection against catastrophic downside risk. This stability allows businesses to budget accurately and plan operations without worrying about unpredictable market swings. Hedging is a crucial element of Essential Risk Management Strategies for Futures Trading Beginners, ensuring businesses focus on their core competencies rather than market timing.

Speculation: Seeking Profit through Directional Bets

Speculation is the offensive use of futures contracts. Unlike hedgers, speculators have no inherent interest in the underlying physical commodity or asset; their sole purpose is to profit from anticipating and correctly predicting the future direction of prices. Speculators are essential risk-takers who accept the uncertainty that hedgers wish to offload.

The Role of Leverage and Liquidity

Speculators use futures because they offer significant leverage. Due to the fractional Margin Requirements in Futures Trading: How Leverage Amplifies Risk and Reward, traders can control large contract values with relatively small amounts of capital. This magnifying effect means small price changes can lead to large profits or large losses.

A speculator engages in two primary actions:

- Going Long: Buying a futures contract if they believe the price of the underlying asset (e.g., Crude Oil or the S&P 500 Index) will rise before expiration.

- Going Short: Selling a futures contract if they believe the price will fall.

Speculators are vital to the health of the futures market because they provide liquidity. By being willing to buy and sell at all times, they ensure that hedgers can easily enter and exit positions, transferring risk efficiently. Understanding the calculation of profit and loss is critical for speculators, as detailed in Calculating P&L in Futures: Real-World Examples Explained for Clarity.

Case Studies: Illustrating the Duality

The contrast between the two primary uses becomes clearest when examining specific market actions.

Case Study 1: The Airline Hedging Fuel Costs

An international airline knows it will need 1 million gallons of jet fuel in six months. The current high price of crude oil poses a threat to its operating margins.

* Action: The airline enters a hedge by buying (going long) enough Crude Oil futures contracts to cover their fuel needs.

* Motivation (Hedging): To protect against rising fuel prices. If crude oil increases 20%, the airline pays more for physical fuel, but they make a corresponding profit on their futures position, neutralizing the cost increase. Their P&L goal is $0—stability is the reward.

Case Study 2: The E-mini S&P 500 Index Speculator

An independent day trader believes the Federal Reserve is about to signal a dovish shift, expecting a resulting rally in the equity market.

* Action: The trader executes a leveraged long position in the E-mini S&P 500 futures contract (Choosing Your Market: A Beginner’s Guide to Index, Commodity, and Currency Futures).

* Motivation (Speculation): To profit from the expected upward movement. If the index rises by 50 points, the highly leveraged contract yields a significant return. The reward is direct profit, but the risk involves losing the initial margin if the prediction is wrong. This action represents pure risk taking, as detailed in A Step-by-Step Walkthrough of Your First Futures Trade Example.

The Symbiotic Relationship and Market Efficiency

While hedgers and speculators have fundamentally different goals, the existence of one group is essential for the function of the other. The futures market is a risk ecosystem where these two groups meet through the centralized mechanism of the exchange and the clearing house (The Role of Clearing Houses and Exchanges in Securing Futures Transactions).

Hedgers initiate the need for risk transfer, creating supply or demand for contracts. Speculators absorb that risk, ensuring that there is always sufficient depth and liquidity in the market to execute trades quickly and efficiently. Speculators also help ensure that the futures price accurately reflects all known information about the underlying asset, contributing to market efficiency.

It is crucial for beginners to recognize their own role. If you are entering the futures market primarily to profit from anticipated price swings, you are speculating and must employ strict risk controls, recognizing the high volatility inherent in directional betting. If you are using futures to lock in a price for an existing physical exposure, you are hedging.

Conclusion

The distinction between hedging and speculation defines the entire landscape of futures trading. Hedging is the conservative practice of using futures to transfer risk and achieve price certainty, essential for commercial operations. Speculation is the aggressive pursuit of profit, driven by directional bets and amplified by leverage. Both roles are necessary, forming a perfect counterparty relationship that creates robust, liquid, and efficient markets. Understanding which role you play is the first step toward building a successful strategy, whether you are managing operational risk or seeking alpha. To delve deeper into the mechanics of futures contracts and risk management frameworks, return to the main guide: The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide to Futures Trading: Contracts, Margin, and Risk Management Explained.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the fundamental difference in intent between a hedger and a speculator?

The hedger’s primary intent is risk reduction; they use futures to lock in a price and avoid exposure to adverse market movements related to an existing physical asset. The speculator’s primary intent is profit generation; they use futures to take a directional bet on future price movement, creating new risk exposure.

Can the same entity sometimes act as both a hedger and a speculator?

Yes. A large commercial entity, such as an energy producer, may use futures to hedge its physical inventory, but its separate trading desk might also take speculative positions based on their market outlook, especially if they believe current futures prices deviate significantly from their perceived fair value.

What type of risk is most critical for a hedger?

The most critical risk for a hedger is basis risk. This is the risk that the price of the futures contract and the price of the physical cash commodity do not move perfectly in sync, meaning the hedge doesn’t perfectly offset the loss in the physical market.

How does speculation benefit the futures market overall?

Speculators provide crucial market liquidity by being willing to take the opposite side of a hedger’s trade. This willingness ensures that hedgers can efficiently transfer risk. Speculation also helps ensure that the current futures price is a fair and efficient reflection of supply, demand, and future expectations.

Does a speculative trade necessarily involve high leverage?

While speculative futures trades often utilize high leverage to maximize potential returns, leverage is not mandatory. However, the use of margin in futures trading allows speculators to control large contract values with minimal capital, which is a major draw for directional traders.

What is an example of a financial hedge?

A portfolio manager expecting a short-term market downturn might sell (go short) Index Futures (like E-mini S&P 500 contracts) to temporarily offset potential losses in their large stock portfolio. This protects the portfolio value without requiring them to liquidate their underlying stock holdings.